Executive Coaching in Law Firms: The Conundrum of ROI

While — notwithstanding the COVID-19 pandemic — the use of executive and leadership coaching within law firms has grown significantly within the last five years, there is still a majority of firms beyond the Am Law 100 where coaching has yet to find its place as a core professional development tool.

Now, let’s imagine that you are in a firm that is interested in adopting or increasing its use of coaching, but your colleagues want to be reassured both of its effectiveness and value.

Unsurprisingly, return on investment (ROI) is a hot topic in the context of coaching. You have read that the oft-cited ICF report (see Resources: ICF) that a median ROI for coaching is 700%. And your friend Google finds a number of other articles on the web that report an ROI of between 500% and 700% with some suggesting a far higher return (see Resources: Returns).

You recognize that if this is accurate, your firm’s CFO cannot help but be impressed. And then, your curiosity sparked, you decide to look for evidence and start to explore the data. First, you look for other research on the ROI of executive coaching. You are intrigued to find a 2005 article on the ICF website entitled, “Measuring ROI in Executive Coaching” (see Resources: Returns). The article argues that developing the ROI in coaching is “very straightforward” using The ROI Methodology. The ROI analysis is standard and is based on the simple formula:

As you think through the formula, you realize that the challenge comes when you are required to clearly and specifically identify the benefits achieved through the coaching program and to attribute a dollar value to those benefits.

Given what you know of coaching, you start to have your doubts about how you would isolate the effects of different types of coaching engagements. After all, in practice, you know enough about the coaching process to understand that many individual and organizational factors can and do impact the outcomes of individual coaching engagements.

And while you are an advocate for the power of coaching and believe it can be effective, you also know that coaching outcomes (or the lack of them) can be the result of factors that have nothing to do with the coaching and that are beyond the control or influence of the coachee.

You decide to go beyond the headlines and explore the research to understand what studies have found about the “straightforwardness” of determining the ROI of coaching. You discover a number of research articles. The first you find is written by Anthony Grant, an Australian professor at the University of Sydney, who founded the world’s first coaching psychology unit and who was a prolific researcher in the coaching arena. Professor Grant argued that ROI is an unreliable and insufficient measure of coaching outcomes and that an over-emphasis on financial returns can restrict an organization’s awareness of the full range of positive outcomes through coaching.

You find other articles pointing out that the reports of ROI are based on small data sets and/ or have been generated by research conducted by or for coaching organizations. You are mindful that there is a good return on the cost of coaching, but rather than take the 700% number at face value, you want to understand it for yourself. The more articles you read, the more you see that discussion of effectiveness and ROI often get collapsed in the literature even though they are, in practice, separate. Working backward, you decide first to explore the issue of effectiveness before you aim to determine what the return on investment is.

Is Coaching Effective? What the Research Says

As you continue googling, you start to feel frustrated. Before you started this exercise, you had assumed that there would be a clear answer to the question of whether executive coaching is effective. The problem, however, is that while coaching organizations make assertions of effectiveness, you cannot help thinking that the articles written by coaches may be self-serving. You switch your attention to academic research to see what support it gives for the blog posts and articles on coaches’ websites.

Digging into the academic research available, it becomes clear that there are no easy answers. You realize that executive coaching is still a developing field of research and that there is no definitive study. To make matters worse, the longer you look, the more disappointed you become. The academic research comes to no clear consensus on the effectiveness of coaching or its ROI despite several major research studies.

As you search for both quantitative and qualitative evidence on the effectiveness of coaching, you compile notes so that you can track what you are reading.

Two researchers at Korn Ferry Institute concluded in a 2009 study (see Resources: Effectiveness) that “the search for ROI appears to be of little practical utility or even necessary.” By using a meta-analysis approach (i.e., reviewing multiple empirical academic studies and analyzing qualitative studies on effectiveness), they found that “coaching works in most cases. Both individual coachees and their organizations benefits.” They also concluded that, “Executive coaching has been used to enhance skills and improve performance in a wide range of organizational arenas,” and “can have tangible and intangible effects on organizational effectiveness to a varying degree.” Nonetheless, you are disappointed that their conclusions about ROI are not positive.

You keep on going and find a study from 2017 (see Resources: Value) that specifically purports to evaluate and systematically review the existing research on the effectiveness of coaching. This sounds promising even though the conclusions are not entirely what you are hoping for.

The researchers identified what they saw as a problem with ROI as a measure. They concluded that ROI — linked to the organization’s financial performance — may not, after all, be the scientific approach to examining effectiveness that so many strive to achieve. In practice, using ROI as a measure requires someone to examine organizational results and to determine how much of the improvement can be attributed to the coaching. Depending on who that “someone” is — should it be the coachee, the sponsor or a key stakeholder — it is exceptionally subjective and carries with it a wide range of reliability and validity issues. With that said, the researchers found that:

Coaching has a moderate positive effect on well-being, work-related attitude, coping strategies, and self-directed goal attainment.

Coaching is an effective tool for improving individuals’ perceptions about themselves and their workplace.

While coaching demonstrably improves the well-being of coachees, it is more difficult to clearly show improved performance. Still, the improved well-being of employees is a positive outcome for the organization (see Resources: Well-Being).

You are more encouraged by a 2018 study that describes itself as the most extensive published analysis on the outcomes of executive coaching (see Resources: Effectiveness). Its authors, who combed through more than 80 peer-reviewed articles, set out to provide a comprehensive review of what is known about the contextual drivers that affect coaching outcomes. The researchers found examples of positive coaching outcomes in 11 different categories, including:

Overcoming regressive behaviors or experiences, e.g., reducing stress and anxiety.

Better personal management and self-control.

Improved personal skills and abilities or acquisition of new ones.

Enhanced leadership skills.

Increased quality of interactions and relationships.

When looking to understand what works, they concluded:

Every coaching model that was tested brought positive outcomes.

A supportive organizational environment and culture contribute to coaching success.

Coaching signals the employer’s support to a coachee; whether that support is real or perceived, it improves coaching impact.

The coach’s timely and effective use of assessment tools improves coaching effectiveness, and vice versa.

Long-term coaching is more effective than short-term coaching.

Impact on performance is stronger for “middle managers” and their subordinates than for “executives.”

The latest study you find — being from 2019 — sounds promising (see Resources: Review). It purports to be “a thorough overview of all qualitative research conducted to date in the field of executive and workplace coaching,” including what the research had demonstrated. The study contrasts qualitative and quantitative approaches. You are disappointed to read the many limitations of qualitative studies. You also note that the researchers in quantitative studies have commonly concluded with reasonable certainty — based on coachees’ perceptions of effectiveness — that coaching sessions were “fairly helpful” in the view of most coachees. This is not exactly the ringing endorsement of coaching that you wanted to find. Somewhat dejectedly, you close your laptop.

By now, you have read multiple articles — written by coaches and coaching organizations — as well as academic studies. There is no definitive answer. In short, there is research-based evidence that coaching can be an effective tool. There is clearly a lot of evidence — some research-based — that coaching “works” (or at least can work). However, the answer to whether there is an ROI is an unsatisfying, if not lawyerly, “it depends.” You have found no compelling model for determining effectiveness or ROI when it comes to coaching. From what you have read, it could be as high as 700% (or even way higher). Then again, it could simply be impossible to calculate.

The Impact of Variables on Coaching Outcomes

You decide that you need to understand what the variables are that impact the effectiveness of coaching. You figure that if you do this, you may be better able to determine who is coachable and who is more likely to have successful outcomes. You will also be better equipped to explain to your colleagues why there’s no easy answer to what the ROI of coaching is.

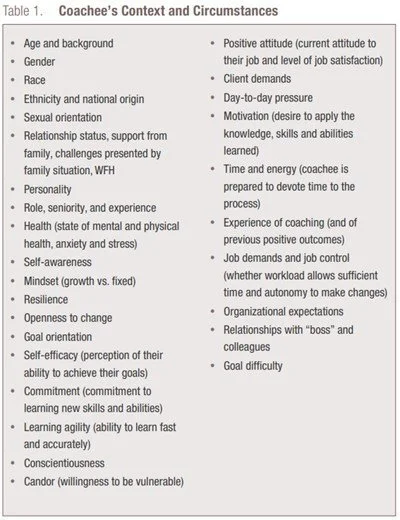

Unlike mentoring, where effectiveness is typically based on the individual’s own assessment and self-reporting, firm-sponsored executive coaching aims to link individual goals with the firm’s strategic and organizational goals. As a result, there are so many variables in play that it can be difficult to take account of all of them, let alone evaluate which are impacting the coaching outcomes. We generally take it for granted that, if we can change the behaviors of leaders and others, the organization, as a whole, will benefit. In law firm coaching, where the coaching is sponsored by the firm (either through the provision of internal coaching support or by paying for an external coach), the coaching relationship is triangulated between coach, client firm (the sponsor), and coaching client (coachee). Despite your enthusiasm for coaching as a professional development tool, you recognize that coaching is not right for everyone and that coaching outcomes can be affected by multiple variables. You sense that when someone wants to change behavior or enhance a skill, it’s more likely that coaching will lead to their doing so than when it is corrective and mandated by the firm. As you reflect on all the ways in which an individual coachee’s context and circumstances may differ, you can see how they could shape a coachee’s perspective and affect the time and energy that they bring to the coaching. You note down as many factors as you can think of (See Table 1).

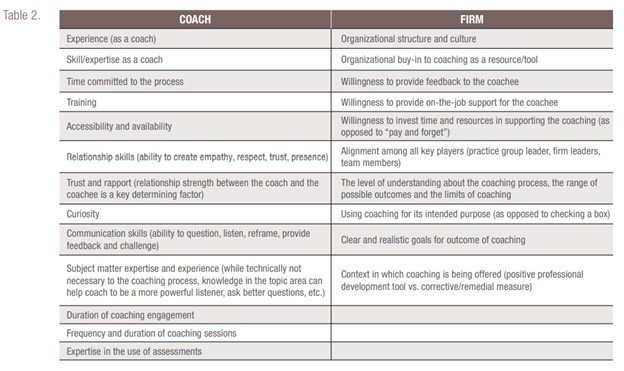

Now that you have what feels like a comprehensive list of the factors impacting a coachee, you take a look at the other two parts of the equations — the coach and the organization. You start jotting down organizational factors and coach-specific factors that can positively affect or inhibit coaching outcomes and play into whether coaching is effective for a given individual.

What you end up with can be seen in Table 2.

Finally, before you wrap up your research, there’s one last academic article you want to read. In it, you learn about the Kirkpatrick model (see Resources: The Kirkpatrick Model) and how it can be used to evaluate coaching outcomes. First developed to evaluate training, the model includes four levels of evaluation. In thinking through how to apply it to coaching, you jot down some questions for coachees:

Level 1: REACTION

How do you feel about the process? How satisfied are you with the coaching experience?

Level 2: LEARNING

How relevant and useful was the coaching? What skills have you developed? What mindset shifts have you experienced?

Level 3: BEHAVIOR

What new skills or changes of behavior have you put into practice as a consequence of the coaching?

Level 4: RESULTS

What is the impact of your new skills and behaviors on your colleagues? What are the results for the firm?

Drawing Conclusions

Having gone through your research exercise, you accept that you may not be able to provide your CFO with a clear verified measure of ROI but, now at least, you feel more confident that coaching is effective in many cases, and you can explain the factors that impact its effectiveness. You are more convinced than ever that coaching can work if it is focused on colleagues who are ready for coaching and ready to do the work involved. You make a mental note to ensure that before sponsoring or requiring coaching for someone, the firm should explore and assess their coachability.

And most importantly, you decide that armed with all the information your research has turned up, you can assure your colleagues that you will track the impact of coaching sponsored by your firm. You plan to do this based on the Kirkpatrick model. As a starting point, you will ask each firm coachee (and their firm sponsor) for a post-engagement evaluation of their coaching and the outcomes. And, where practicable, you will experiment with isolating specific direct benefits of coaching and their dollar value and see if you can calculate an ROI. After all, even half of 700% would seem like a great result!

A Final Note on Coaching Effectiveness: What Law Firms Say

A conversation about law firm coaching and effectiveness and ROI would be incomplete without mentioning the findings from our own research at Volta. The Volta Coaching Insights Survey, which is the only industry-specific survey, explores the use of coaching in law firms in the U.S. In our 2021 survey, 72 law firms participated, including 41 Am Law 100 firms.

Our research found that a significant majority of firms using coaching (72%) see it as “extremely effective” or “very effective” in achieving individual goals. When it comes to achieving organizational goals, a majority of firms- albeit not as overwhelming at 56% — view coaching as “extremely effective” or “very effective.”

These numbers are encouraging since at the beginning of the pandemic, it seemed as if all the progress in law firm coaching might be set back significantly. However, the economic resilience and success of law firms during the pandemic — combined with the versatility of coaching as a tool and its ability to address highly individualized and adaptive challenges — led to coaching bouncing back far sooner than anticipated.

RESOURCES

ICF

ICF Global Coaching Client Study Final Report, June 2009, published by the International Coaching Federation and Pricewaterhouse Coopers LLP.

Returns

“Maximizing the Impact of Executive Coaching: Behavioral Change, Organizational Outcomes, and Return on Investment,” published in The Manchester Review, 2001, estimated that ROI averaged nearly 5.7 times the initial investment in coaching.

“Business impact of executive coaching: demonstrating monetary value,” Vernita Parker-Wilkins, Industrial and Commercial Training, 2006, Vol. 38 Iss. 3 pp. 122-127, found an ROI of 689 percent.

“Executive Briefing: Case Study on the Return on Investment of Executive Coaching,” MetrixGlobal, LLC. Merrill C. Anderson, PhD, November 2, 2001.

"Measuring ROI in Executive Coaching," Jack J. Phillips and Patricia P. Phillips, The International Journal of Coaching in Organizations, 2005, 3(1), 53-62 "ROI is a poor measure of coaching success: Towards a more holistic approach using a well-being and engagement framework," Anthony M. Grant, September 2012, Coaching An International Journal of Theory Research and Practice 5(2):1-12

Effectiveness

“The Effectiveness of Executive Coaching: What We Can Learn From The Research Literature,” Kenneth De Meuse and Guangdong Dai, Korn/Ferry Institute, 2009

“A Systematic Review of Executive Coaching Outcomes: Is It The Journey or The Destination That Matters Most,” Dr. Andromachi Athanasopoulou and Professor Sue Dopson, February 2018, The Leadership Quarterly 29(1).

“Coaching in the wild: Identifying factors that lead to success,” Shirley C. Sonesh, University of Central Florida, Chris W. Coultas, Leadership Worth Following, LLC, Irving, Texas, Shannon L. Marlow, Christina N. Lacerenza, Denise Reyes, and Eduardo Salas, Rice University, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, American Psychological Association 2015, Vol. 67, No. 3, 189–217.

Value

“The unsolved value of executive coaching: A meta-analysis of outcomes using randomized control trial studies,” conducted by Australian psychologists and academic researchers Daniel Burt and Zenobia Talati, from Murdoch University and Curtin University respectively. The study was published in the International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, Vol. 15, No. 2, August 2017.

Well-Being

“Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context,” T Theeboom, B Beersma and A E van Vianen (2014), The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(1), 1-18

“Does executive coaching work: A meta-analysis study,” K DeMeuse, G Dai and R Lee (2009), Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Practice and Research, 2(2), 117-134

Review

“A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies in Workplace and Executive Coaching: The Emergence of a Body of Research,” Erik de Haan, Hult International Business School, Consulting Psychology Journal, 71.4, 227-248, 2019.

The Kirkpatrick Model

*Evaluating training programs*: The four levels, Donald L. Kirkpatrick and John Kirkpatrick, 2006, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehle

This article first appeared in the November 2021 Digital Edition of the National Association for Law Placement (NALP) Bulletin+ on November 2, 2021. All rights reserved by NALP.